The Story Behind: I Heard the Bells On Christmas Day

Peace seems impossible when suffering surrounds us. The Christmas bells ring out their message of hope, yet our hearts often struggle to believe. Such was the case for Henry Wadsworth Longfellow when he penned one of Christianity’s most poignant Christmas carols – a hymn born from the depths of personal tragedy and national strife.

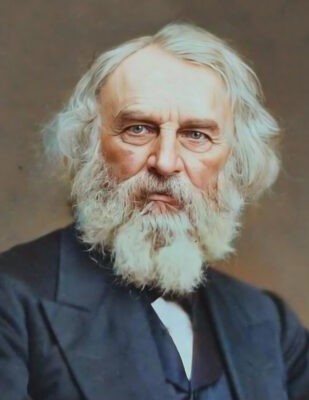

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow: Early Life and Family

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was already one of America’s most celebrated poets when tragedy began to shape his greatest hymn. Born in 1807, he had built both a successful career and a loving family in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His colonial mansion, which had served as General Washington’s headquarters during the Revolutionary War from 1775 to 1776, was home to him, his beloved wife Fanny Elizabeth Appleton, and their six children. Together they raised Charles (their eldest, born June 9, 1844), Ernest, and four daughters—though one daughter had tragically died in infancy. But neither literary acclaim nor historical surroundings could shield him from the storms approaching.

Personal Tragedy: The Death of Fanny Longfellow

The first blow came in July 1861. Fanny was sealing envelopes with hot wax when her dress caught fire. Henry, awakened from a nap, rushed to help. He desperately tried to extinguish the flames, first with a rug and then with his own body, but the damage was already done. Fanny died the next morning, July 10, 1861. Henry’s burns were so severe he couldn’t even attend his wife’s funeral. The physical scars forced him to grow a beard – an image that would become his trademark – but the emotional scars ran far deeper. At times, his grief was so overwhelming that he feared being sent to an asylum. He would write in his journal, “I can make no record of these days. Better leave them wrapped in silence. Perhaps some day God will give me peace.””

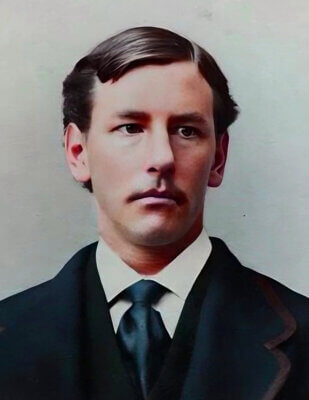

Civil War: Charles “Charley” Longfellow Joins the Union Army

Upon his arrival, Captain W. H. McCartney, commander of Battery A, wrote to Longfellow requesting permission for Charley to serve. Though his father eventually gave his consent, he worked tirelessly behind the scenes, writing to influential friends including Senator Charles Sumner and Governor John Andrew of Massachusetts, hoping to secure his son an officer’s position. Charley’s natural abilities proved more persuasive than his father’s letters – his skills so impressed his fellow soldiers and superiors that by March 27, 1863, he was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry, assigned to Company “G”.

The young lieutenant’s early military career was marked by both close calls and setbacks. At the Battle of Chancellorsville in Virginia (April 30-May 6, 1863), he was assigned to guard supply wagons rather than seeing combat. That summer, he fell ill with “camp fever” – likely typhoid – missing the pivotal Battle of Gettysburg while recovering at home. But his father’s fears proved prophetic when, after rejoining his unit on August 15, disaster struck. During a skirmish in the Mine Run Campaign on November 27, 1863, Charles was shot through the left shoulder. The bullet exited under his right shoulder blade, crossing his back and missing his spine by less than an inch – a hair’s breadth from paralysis.

Charles was first carried into New Hope Church in Orange County, Virginia, then transported to the Rapidan River. When the telegram reached Longfellow on December 1, it erroneously reported his son had been shot in the face. The anxious father and his younger son Ernest immediately set out for Washington, arriving December 3. When Charles arrived by train two days later, three army surgeons offered cautious hope – though the wound was serious, they predicted a full but lengthy recovery of at least six months.

Christmas 1864: The Birth of I Heard the Bells On Christmas Day

It was against this backdrop of personal pain and national division that Longfellow sat alone on Christmas Day 1864, a 57-year-old widowed father of six, his eldest son still healing from near-paralysis as his nation bled. The bells of Cambridge rang out their yearly message of “peace on earth, good will to men,” but the words seemed to mock the reality of his world. Yet as he listened, something profound began to stir in his poet’s heart. The resulting verses would move from despair to defiant hope:

I heard the bells on Christmas day

Their old familiar carols play,

And wild and sweet the words repeat

Of peace on earth, good will to men.

But Longfellow didn’t shy away from his doubts, penning what many hymn writers might have avoided:

And in despair I bowed my head

“There is no peace on earth,” I said,

“For hate is strong and mocks the song

Of peace on earth, good will to men.”

Yet the bells kept ringing, and with them came a profound realization that God’s truth would prevail:

Then pealed the bells more loud and deep:

“God is not dead, nor doth He sleep;

The wrong shall fail, the right prevail

With peace on earth, good will to men.”

The Crosby Connection

In 1956, the hymn found new life through an unexpected collaboration. Johnny Marks, already famous for writing “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” and “Rockin’ Around the Christmas Tree,” composed a new melody for Longfellow’s timeless words. Bing Crosby recorded the song on October 3, 1956, using verses 1, 2, 6, and 7 of the original poem. The recording was an immediate success, reaching No. 55 in the Music Vendor survey and earning high praise from both Billboard and Variety. Crosby, impressed by Longfellow’s powerful lyrics, quipped to Marks, “I see you finally got yourself a decent lyricist.”

When Bells Keep Ringing

Before Marks’s version, English organist John Baptiste Calkin had set the poem to music in 1872 using his melody WALTHAM, transforming Longfellow’s private reflections into a public declaration of hope. Today, both melodies continue to touch hearts, with Marks’s version becoming particularly popular through recordings by artists from Johnny Cash to modern performers.

“I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day” endures because it speaks honestly to the human struggle between faith and doubt. Like the prophet Habakkuk who questioned God yet chose to rejoice, Longfellow’s hymn acknowledges the reality of suffering while ultimately declaring God’s sovereignty. When the world seems darkest, when peace seems furthest away, the bells still ring out their defiant message of hope.

Perhaps that’s why this carol, born from the crucible of personal and national tragedy, continues to resonate. In a world still plagued by division and strife, Longfellow’s journey from despair to hope reminds us that God is indeed “not dead, nor doth He sleep.” The Christmas bells still ring, and their message remains unchanged: in God’s time, wrong shall fail, right prevail, with peace on earth, good will to men.

Frequently Asked Questions:

Q: What is the significance of bells at Christmas?

A: Church bells have been used to herald important Christian celebrations since medieval times, with Christmas bells specifically calling people to worship the newborn King. The joyful ringing symbolizes heaven’s announcement of Christ’s birth, echoing the angels who proclaimed the good news to the shepherds.

Q: What is the story behind the hymn “I heard the bells on Christmas Day”?

A: Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote this hymn on Christmas Day 1864 after suffering two devastating blows – his wife’s tragic death in a fire and his son’s severe wounding in the Civil War. The contrast between the joyful Christmas bells and his personal sorrow, combined with the nation’s turmoil, inspired him to write a poem that moves from despair to triumphant hope in God’s providence.

“I Heard the Bells On Christmas Day” Lyrics Video

Download sheet music, chord charts, tracks and multitracks for I Heard the Bells On Christmas Day exclusively here at Hymncharts.com and WorshipHymns.com. You won’t find this arrangement on any other websites.