The Story Behind: At the Cross

At the Cross: A Tale of Two Creations

Too often when singing a familiar hymn, we fail to consider the hands through which it passed before reaching our lips. So it is with “At the Cross,” a hymn whose journey spans two centuries and represents the creative efforts of multiple people. What began as a solemn reflection on Christ’s sacrifice would, nearly two centuries later, be transformed into one of evangelicalism’s most beloved songs through the addition of a joyful refrain.

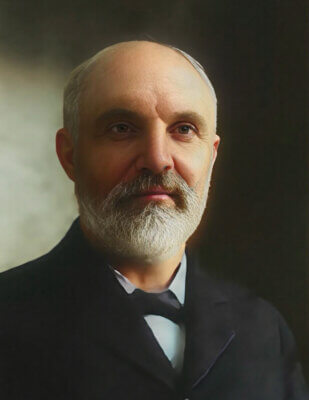

Isaac Watts: the Father of English Hymnody

Isaac Watts was born in Southampton, England in 1674, the oldest of nine children. His father, a committed Nonconformist preacher, was imprisoned twice for his religious convictions, refusing to conform to the Church of England which he believed had not sufficiently separated from Roman Catholic doctrines.

From his earliest days, young Isaac was immersed in Scripture—his father would regularly read God’s Word to him and pray over him, later instructing all his children “frequently to read the Scriptures – get your hearts to delight in them – above all books and writings account the Bible the best and read it most – lay up the truth of it in your hearts.”

This Biblical foundation served Isaac well. By age fifteen he had committed his life to Christ, and by sixteen had mastered Latin, Greek, Hebrew, and French. His intellectual gifts were evident, but it was his dissatisfaction with congregational singing that would ultimately lead to his greatest contribution to the church. This contribution would eventually earn him the title “Father of English Hymnody,” and his work would go on to inspire poets such as Charles Wesley, William Blake, and Emily Dickinson.

A Father’s Challenge

At around twenty years of age, Isaac became increasingly frustrated with the quality of songs being sung in Nonconformist congregations. At that time, most church singing was limited to metrical Psalters and direct Scripture quotations, as many Protestants following John Calvin’s teaching believed it sinful to sing anything not taken directly from the Bible. When Isaac complained about the poor quality of these songs, his father issued a challenge: if he didn’t like what was being sung, perhaps he should create something better.

That challenge sparked a remarkable period of creativity. Between the ages of twenty and twenty-two, Isaac wrote many of the approximately 600-750 hymns he would compose in his lifetime, including classics such as “Joy to the World,” “When I Survey the Wondrous Cross,” and “O God, Our Help in Ages Past.” His new approach to hymn writing wasn’t welcomed by all. His own father reportedly told him, “That old hymnal was good enough for your grandfather, and your father, and so I reckon it will have to be good enough for you!”

The objections weren’t merely about tradition but centered on a fundamental disagreement about the proper content of worship songs. Isaac’s response was simple but profound: “…if we can pray to God in sentences that we have made up ourselves (instead of confining ourselves to the Our Father and other prayers taken directly from the Scriptures), then surely we can sing to God in sentences that we have made up ourselves.”

For Such a Worm as I

In 1707, Isaac published a collection titled “Hymns and Spiritual Songs,” which included the hymn “Alas! and Did My Saviour Bleed.” The original version consisted of six stanzas with no refrain, and began with these powerful words:

Alas! and did my Saviour bleed?

And did my Sovereign die?

Would He devote that sacred head

For such a worm as I?

The final line of the first stanza—”For such a worm as I”—has stirred controversy in modern times, with many hymnals changing “worm” to “one” or revising the line to “for sinners such as I.” Critics suggest it promotes unhealthy self-deprecation, but defenders point to the biblical roots of the imagery, likely drawn from Psalm 22:6 (“But I am a worm, and no man; a reproach of men, and despised of the people”), a psalm prophetically connected to Christ’s crucifixion. In referring to himself as a “worm,” Watts was highlighting the vast contrast between the majestic Savior and the lowly sinner.

From Poem to Hymn

Watts wrote his hymns as poems meant to be sung to a variety of tunes, and we don’t know what melody was originally used with “Alas! and Did My Saviour Bleed.” By 1800, it was frequently paired with the tune “Martyrdom,” composed by Hugh Wilson based on an old Scottish melody. The hymn found widespread use in Great Britain and even greater popularity in America, where it would eventually become the foundation for a new creation.

Fanny Crosby’s November Experience

One particularly powerful testimony of the hymn’s impact comes from Fanny Crosby, the renowned blind hymn writer. In November 1850, at the age of thirty, Crosby was seeking a deeper relationship with the Lord and attended revival meetings at the Broadway Tabernacle in New York. When the congregation began singing “Alas! and Did My Saviour Bleed?” and reached the words “Here, Lord, I give myself away,” Crosby experienced what she called her “November Experience.”

In her own words: “It seemed to me that the light must indeed come then or never; and so I arose and went to the altar alone… And when they reached the third line of the fourth stanza, ‘Here Lord, I give myself away,’ my very soul was flooded with a celestial light. I sprang to my feet, shouting ‘hallelujah,’ and then for the first time I realized that I had been trying to hold the world in one hand and the Lord in the other.”

Ralph E. Hudson: the Methodist Evangelist

While Watts’ profound lyrics continued to touch hearts throughout the 19th century, the hymn we know today as “At the Cross” wouldn’t emerge until 1885. This transformation came through Ralph E. Hudson, an American preacher, gospel singer, and publisher.

Hudson was an active evangelist in the Methodist Episcopal Church and often participated in camp meetings—outdoor revival gatherings popular in 19th century America. These spirited meetings were characterized by emotional preaching and lively congregational singing that contrasted with the more formal church services of the day.

A Borrowed Refrain

What many people don’t realize is that Hudson didn’t create the entire song from scratch. The familiar refrain that begins “At the cross, at the cross, where I first saw the light” has its own fascinating history. Its melodic roots trace back to a secular song called “Take Me Home,” originally published in 1853 with lyrics that began “Take me home to the place where I first saw the light, to the sweet sunny south take me home.”

This tune underwent a spiritual transformation at the hands of the Salvation Army in England in the early 1880s. The earliest documented use appears in The Luton Reporter from April 28, 1883, which described a Salvation Army meeting led by General William Booth where a participant sang:

“At the cross, at the cross, when I first saw the light,… And the burden of my heart rolled away, It was there by faith I received my sight, And now I rejoice night and day.”

The refrain subsequently made its way to America through Salvation Army missions. The earliest documented American example comes from September 1884, when The Weekly Bee in Sacramento, California, described Salvation Army members singing the refrain during a meeting. The article explicitly noted the connection to the secular song, reporting that the audience sang “a hymn to the tune of ‘Take me back to my home in my own sunny south,’” with the chorus containing the now-familiar “At the cross” refrain.

Two Become One

Hudson’s significant contribution was not just combining Isaac Watts’ powerful text with this popular refrain. Unlike previous arrangements that typically used the same melody for both the stanzas and refrain, Hudson created a new melody specifically for Watts’ verses, giving the song a proper verse-chorus musical structure. In 1885, he published this arrangement in his songbook “Songs of Peace, Love, and Joy,” using the final line “happy all the day” rather than the “rejoice night and day” variant that had circulated in some Salvation Army circles.

The result was a perfect marriage of Watts’ profound theological reflection with the joyful testimony of the refrain:

At the cross, at the cross, where I first saw the light,

And the burden of my heart rolled away,

It was there by faith I received my sight,

And now I am happy all the day!

Two Centuries, Two Expressions

Hudson’s arrangement transformed the solemn meditation on Christ’s suffering into a more celebratory testimony of salvation found at the cross. While some traditional hymnologists might have considered this alteration to Watts’ original work unnecessary, the new version resonated deeply with American evangelicals. The addition of the refrain shifted the focus somewhat from Christ’s suffering to the believer’s joyful response—from what happened at Calvary to what happens in a person’s heart when they encounter the cross.

Both versions of the hymn—Watts’ original “Alas! and Did My Saviour Bleed” and Hudson’s adaptation “At the Cross”—continue to appear side-by-side in many hymnals today. Each version serves a different purpose in worship: one leads us to solemnly contemplate Christ’s sacrifice, while the other celebrates the joy and freedom that sacrifice brings.

The enduring popularity of “At the Cross” reminds us that sometimes the greatest expressions of faith emerge not from a single creative moment, but through a process of adaptation and development spanning generations. What began as Isaac Watts’ theological reflection in 1707 was transformed through Ralph Hudson’s musical adaptation in 1885 into a testimony of personal salvation that continues to move hearts today.

As the prophet Isaiah wrote centuries before either Watts or Hudson put pen to paper: “But he was wounded for our transgressions, he was bruised for our iniquities: the chastisement of our peace was upon him; and with his stripes we are healed. All we like sheep have gone astray; we have turned every one to his own way; and the Lord hath laid on him the iniquity of us all” (Isaiah 53:5-6). Both versions of this beloved hymn point us to this eternal truth.

Frequently Asked Questions:

Q: What is the origin of the song “At the Cross”?

A: “At the Cross” originated from Isaac Watts’ 1707 hymn “Alas! and Did My Saviour Bleed.” In 1885, Ralph Hudson transformed it by adding a popular revival refrain from Salvation Army meetings and composing a new melody for Watts’ verses, creating the beloved version sung today.

Q: What is the story behind the cross?

A: The cross represents Jesus Christ’s crucifixion at Calvary, where He died to atone for humanity’s sins according to Christian belief. This Roman method of execution became Christianity’s central symbol because believers see it as the place where divine justice and mercy met, offering salvation through Christ’s sacrificial death.

“At the Cross” Lyrics Video

Download sheet music, chord charts, tracks and multitracks for At the Cross exclusively here at Hymncharts.com and WorshipHymns.com. You won’t find this arrangement on any other websites.